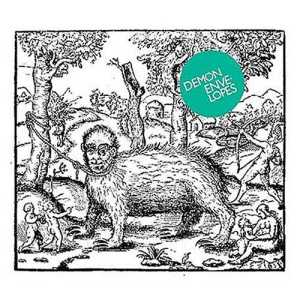

No Pop No Stars Corner: Envelopes - 'Demon' - Cool Album.

Pop bands that deconstruct pop music are nothing new. But rarely are they this good. On first listen, I was ready to dismiss Envelopes, to relegate them to the “too smart and self-conscious to be meaningful beyond being hip” category. Name your favorite band and there are elements of said band on Demon. Talking Heads? Yes. Pixies? Definitely. Velvet Underground? Of course. Hazelwood, Stereolab, Magnetic Fields? Yep, yep, and yep. In addition to the artistic reference points, the album sounds like the great indie releases of ‘80s underground (Beat Happening, et al), and has the hipster checkpoints of male/female vocals and a Moog.

Pop bands that deconstruct pop music are nothing new. But rarely are they this good. On first listen, I was ready to dismiss Envelopes, to relegate them to the “too smart and self-conscious to be meaningful beyond being hip” category. Name your favorite band and there are elements of said band on Demon. Talking Heads? Yes. Pixies? Definitely. Velvet Underground? Of course. Hazelwood, Stereolab, Magnetic Fields? Yep, yep, and yep. In addition to the artistic reference points, the album sounds like the great indie releases of ‘80s underground (Beat Happening, et al), and has the hipster checkpoints of male/female vocals and a Moog."Sister In Love"

Now, this review is like a Choose-Your-Own Adventure novel. If the above description made you feel super-excited to hear Envelopes, this album will be a perfect 10 for you. Stop reading and go buy the import version of the album to get that “I had it as an import!” edge on your friends. If the above description made you roll your eyes and/or yawn, keep reading. First things first: the DIY sound of the record is not, necessarily, a gimmick. The 11 songs on the record are in fact demos recorded by the band themselves in a rented house in the English Countryside. Demon is Swedish for demo, which makes sense, since the tracks are demos and the band is 4/5’s Swedish, also serving to absolve Envelopes of a trite Beelzebub reference.

The three opening tracks, “It Is the Law”, “Glue”, and “Sister in Love”, are no doubt the most indie-friendly and/or the catchiest songs on the record. They will probably be the tracks that get the band the most notice; it is the rest of Demon that (will) justify the attention. The fourth track is where things start to get interesting. "Your Fight Is Over” is a wistful melody, gentle pop tune in the vein of Belle and Sebastian, and that great track is immediately followed by "I Don’t Even Know”, another strongly crafted pop tune with a jagged guitar hook and some delicious "whoa oh whaa oh… hey!” backing vox. This one-two (or four-five?) punch is where Envelopes begin to distinguish themselves from all the other bands that can write a catchy indie single like "Sister in Love”.

"Audrey in the Country" is the offspring of The Velvet Underground’s "After Hours” but it’s still well executed and serves as a nice lead-in to the meat of the disc, the sequence of "My Fren", followed by "I Don’t Like It”. Then comes the album’ standout track, “Massouvement”, which is firmly planted in Hazelwood/Sinatra territory, but bouncier and with tasty slide guitar lines. The final track, "Sotnos”, is John Cale "Amsterdam"-ish, but no matter. By track 11, the Envelopes have proven that they are far beyond pastiche without comment or emulation without improvement. They’ll no doubt attract a great deal of press and indie-love in 2006, and it will be much deserved. Time will tell if the Envelopes were merely able to muster up one great album or if this is but the beginning of an artistically progressive career. But either way, Demon is a stellar debut album.

"Audrey in the Country" is the offspring of The Velvet Underground’s "After Hours” but it’s still well executed and serves as a nice lead-in to the meat of the disc, the sequence of "My Fren", followed by "I Don’t Like It”. Then comes the album’ standout track, “Massouvement”, which is firmly planted in Hazelwood/Sinatra territory, but bouncier and with tasty slide guitar lines. The final track, "Sotnos”, is John Cale "Amsterdam"-ish, but no matter. By track 11, the Envelopes have proven that they are far beyond pastiche without comment or emulation without improvement. They’ll no doubt attract a great deal of press and indie-love in 2006, and it will be much deserved. Time will tell if the Envelopes were merely able to muster up one great album or if this is but the beginning of an artistically progressive career. But either way, Demon is a stellar debut album.RATING:8

Text By Ryan Gillespie - Pop Matters

Envelopes Home Page

My Space